Delay in reaching tecovirimat, the only drug approved by the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) for the treatment of monkeypox, can cause the disease to progress unchecked and with atypical ophthalmic manifestations. This has occurred in at least ten patients with monkeypox (or Mpoxid) in São Paulo, who were treated by Luciana Vinamor, an ophthalmologist who specializes in eye infections.

In two of them, waiting for the medication for 60 days caused blindness in one eye, a condition that the existing literature doesn’t yet know how to determine if it can be reversed.

The last shipment of tecovirimat that arrived in Brazil brought the treatments of two patients in São Paulo, who were treated in the public network, and who were accompanied by the report. In both, monkeypox developed without specific viral treatment for two months and in an insidious manner, transferring the lesions from the skin to the cornea and compromising the vision of both to the point of blindness.

Cases of ocular monkeypox are still rare, but have been documented. In a report released in October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, in its original English acronym) warned the US that the disease could cause “serious complications” in the eyes, with five cases recorded in the country between August and September, all treated with tecovirimat. .

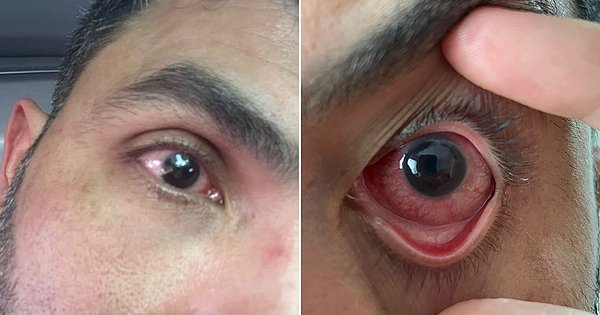

Signs appear after skin ulcers have partially or completely healed, about 15 to 40 days after the onset of the most common symptoms, such as fever, pain, and fatigue. It begins as irritation in the eye, which can become watery, reddish with a strong sensitivity to light and a feeling of sand behind the eyelid, which can progress to vision loss.

“Although few, these cases make us anxious because we have tried every possibility and we have not been able to cure it. The patient simply does not get better,” says doctor Luciana Vinamor, specialist in eye infections at the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp). “Therefore, it is important to have access to antivirals, so that we can fight the disease better.”

One of the hypotheses of this case is self-inoculation caused by the patients themselves, who transmit the virus to the eye by scratching the wounds and then touching their face. Another possibility is that the eye, as an immune-privileged organ, allows the virus to remain “hidden” until it causes a chronic inflammatory condition that is impossible to fight with natural antibodies alone.

“Today, I only see numbers,” says Paolo (fictitious name), a 37-year-old restaurant manager that Luciana attends, whose eye damage from monkeypox began to appear 27 days after the first signs of illness appeared. Initial symptoms were fever, pain, and blisters in the hand, mouth, and arm on September 7.

About a week after feeling the first irritation in his eye, Paolo went to an ophthalmologist, who advised him to use a combination of eye drops, which had no effect. He went to a second specialist, who this time started treating herpes zoster. It was already mid-October and it had been 20 days since his eye symptoms appeared when he finally got the correct diagnosis.

“I saw a few, but the discomfort was enormous,” he says. “Photophobia was present (at the onset of the disease), but it is not as severe as it is today. I was able to drive to appointments, and today I no longer drive. I have lost the reflection on my left side because of the eye; I can’t even see in the rearview mirror. I can’t go out in the sun either, I start crying.

History repeated itself with Felipe (not his real name), a 42-year-old doctor, who also took 22 days to confirm that the eye irritation was a result of monkeypox, which he was diagnosed with on August 30. “I had a very serious deterioration. There were days when I couldn’t see anything. My eyes became so red, I couldn’t look at the light. I had to stay in a darkened room because even the light from the cell phone and TV caused me pain.”

Without access to tecovirimat, Felipe began using a combination of medications to relieve the pain and irritation of his eyes, with hydrating eye drops and gel, an eye ointment for sleep, a second eye drop dripped every hour and a third, an antibiotic, applied every six hours. Although he works in the medical field, he says he “lived for his eyes” and had to take time off from work, but he told the reason only to his immediate superiors.

“Most people don’t know it’s caused by monkeypox,” he says. “There’s still a lot of stigma out there that can lead to my complications.” “But I was so scared because I knew I wasn’t being treated as well as I should have been, and I thought I was going to go blind or lose my eyes or need a cornea transplant.”

Paolo and Felipe spoke to the reporter in November, three days before the second shipment of tecovirimat arrived in Brazil, and when they did not even know if it would happen or would have an effect today, a month after the start of treatment, the future is still not guaranteed an uncertain and complete reversal to damage the eye. Although they are well developed, they both have scars on their corneas and it is likely that they will need a transplant to fully restore their sight.

“We cannot abandon this because the disease has a natural course in the body. But, based on what we see in the world literature, at least in the ophthalmological picture, tecovirimat helps,” comments Luciana. “We still haven’t seen serious eye cases like here in Brazil, because in other countries they use antivirals much earlier, at the onset of symptoms.”

In response to a question from Estadão, the Ministry of Health reported that the criteria for access to tecovirimat are a positive laboratory result with a visible lesion or a hospitalized patient with the acute form of infection. For this second group, the presence of the following clinical manifestations is considered: encephalitis, pneumonia, skin lesions with more than 250 rashes throughout the body, extensive lesion of the oral mucosa and/or extensive lesion of the rectal mucosa.

According to the file, 28 treatments have been delivered to Brazil so far through donations from the World Health Organization and the manufacturer. Of these, 16 arrived in November, 10 of which were referred directly to eligible patients.

In a note, the São Paulo State Secretariat of Health (SES) reports that it has received 11 requests for treatment with tecovirimat during the current outbreak of monkeypox. The volume also claims to follow the Ministry of Health’s clinical definition and care protocol for cases of the ocular manifestation of disease.

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”