Nearly three million people worldwide suffer from multiple sclerosis (MS). Some scientists believe that they have discovered the cause of this incurable disease. They think it’s a virus that we can almost all catch. But what does this mean for the treatment and prevention of MS?

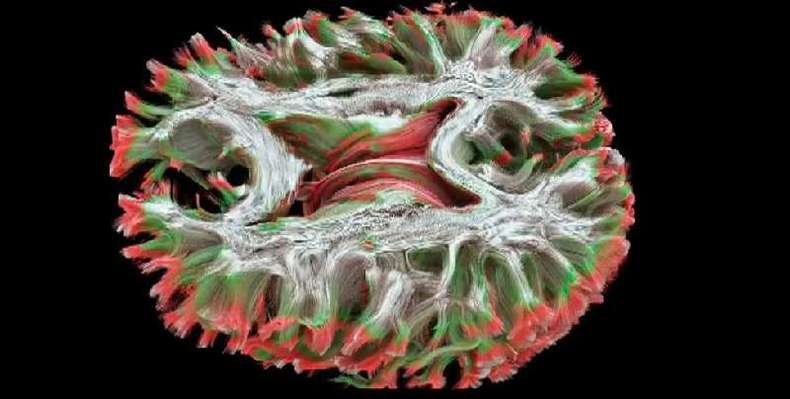

Our brains are like an “orchestra” of electrical activity. Billions of “individuals”, neurons, produce minute electrical signals. When they come together, the resulting symphony is who we are, our thoughts, our emotions, our control over our bodies, and how we experience the world around us.

But in multiple sclerosis, there’s a saboteur at work. Our immune system turns against neurons and they can no longer play in tune. The result can be devastating.

What triggers the immune system to act in this way has been a long and controversial mystery, but studies published this year have convincingly pointed to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

“It is very strong evidence that this virus may be the cause of MS,” Professor Gavin Giovannini of Queen Mary University of London told the BBC.

detective work

The Epstein-Barr virus is so common that almost all of us can expect to have it in our lifetime. Most of us won’t even notice, but the virus is notorious for the “kissing disease,” which is also known as glandular fever or mononucleosis.

EBV has been on the list of suspected MS for decades, but definitive proof is hard to come by because the virus is so common and multiple sclerosis is rare.

Crucial evidence came from the US Army, which takes blood samples from soldiers every two years. The samples are kept in the refrigerators of the Department of Defense’s serum and turned out to be a goldmine for researchers.

A team from Harvard University analyzed samples from 10 million people to establish the link between EBV and multiple sclerosis.

The study, published in Science, found that 955 people were diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and, using regular blood samples, were able to trace the course of the disease.

“Individuals who have not had the Epstein-Barr virus never develop multiple sclerosis,” says Alberto Acchirio of Harvard University.

“Only after infection with the Epstein-Barr virus increases the risk of developing multiple sclerosis by more than 30 times.”

The team checked for other infections, such as cytomegalovirus, but only EBV had a clear link to the neurodegenerative disease.

Some soldiers have contracted the virus. Signs of brain damage – called neuropeptides, which are essentially the remains of damaged brain cells – began to appear in the blood. They were diagnosed with MS about five years after the injury.

Ascherio says the study is the “first” convincing evidence that EBV causes disease. He said it was “very common” for viruses to infect many people but only cause serious complications in a few. For example, in the world before vaccinations, “almost every child” had polio, but one in 400 did.

But how do you make sure?

To prove that the virus plays a critical role in the disease, it is necessary to do a study that can prevent people from contracting EBV — and see if that prevents multiple sclerosis.

Currently, research is underway to detect what the virus does inside the body.

If we focus on a single neuron – just an instrument in the brain’s orchestra – it is coated with a fatty layer of insulation called the myelin sheath. It is this fatty layer that allows electrical signals to reach neurons at a speed of 100 meters per second. But in multiple sclerosis, the immune system attacks myelin, disrupting electrical messages and damaging nerve cells.

Depending on the affected part of the brain or spinal cord, multiple sclerosis can lead to numbness, blurred vision, difficulty walking, slurred speech, and problems with memory or emotions.

Professor Bill Robinson, an immunologist at Stanford University in California, was a skeptic about EBV until a few years ago. “I didn’t take it seriously, everyone has EBV, so there’s no way this could be a cause of MS.”

Now he is completely convinced of this connection. He thinks he may be able to join the points between the virus and the myelin sheath.

Their study, published in Nature, showed that the myelin sheath is misidentified and under attack by a confused part of the immune system thought to be fighting EBV.

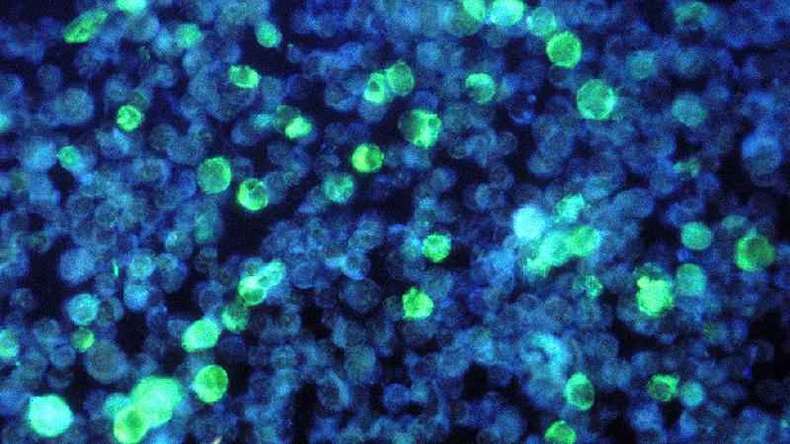

His team was looking at B cells, the part of the immune system that makes antibodies to look for viruses and other threats. These antibodies attach to the gas and signal the rest of the immune system to attack.

In MS patients, they found that antibodies designed to attack part of the virus (a protein called EBNA1) could also bind to a human protein in the brain (called GlialCAM). This state of misidentification is known, at the molecular level, scientifically as cross-reactivity.

“[O vírus] It stimulates cross-interaction of a viral protein also similar to the myelin sheath protein, resulting in damage that causes MS symptoms,” says Professor Robinson.

Obviously, this does not happen to everyone who has been infected with EBV. Other factors may play a role in the disease: being female, having some childhood trauma, and low levels of vitamin D (from being born in a place with little sunlight) all increase the risk of developing MS.

Is there some form of prevention?

A clearer picture of the cause of MS gives a better idea of how to treat or even prevent it.

The big vision is to replicate the success of the fight against the cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV). Infection with HPV can increase the risk of cancer, including cancer of the cervix, penis, and mouth. But the childhood vaccination program has had such a profound impact on cancers that the old routine of regular checkups is no longer necessary.

There are several companies already working on an EBV vaccine, including Moderna, which is using the same technology used to develop the Covid vaccine. However, vaccinations will need to stop the immune system from producing the same harmful antibodies as multiple sclerosis.

Knowing whether a vaccine can prevent multiple sclerosis will take decades of work. Another ambition is to create a “cure vaccine” for people who already have MS.

Giovannini said the vaccine would be similar to the one used against shingles (or shingles), which is given to people who have already had the chickenpox virus.

“Even if you already have the virus, you stimulate the immune system to create an immune response against the virus and take control of the virus itself,” he says.

Therapies that target EBV-infected B cells — and drugs that attack the virus itself — are also being researched. Some studies suggest that HIV drugs reduce the risk of developing multiple sclerosis, Giovannini says, which may be a way forward.

But there are still great doubts. Once you’ve been infected with EBV, you have it in your body for life – it lodges in the antibody-producing B cells.

So, is it the primary infection that puts the immune system on the wrong track? Or does the continued presence of the virus affect the immune system and lead to multiple sclerosis?

Researchers have made great strides in understanding the causes of multiple sclerosis, but harnessing this knowledge to change people’s lives remains a challenge.

Did you know that the BBC is also on Telegram? Subscribe in the channel.

Have you seen our new videos on Youtube? Subscribe to our channel!

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”