Scientists from the US Fermilab Laboratory believe they are closer to discovering the fifth force of nature, after they found new scientific evidence that particles called “muons” do not behave as expected in the current theory of subatomic physics. Meaning, physicists believe that a new, unknown force may be affecting these particles.

“We’re talking about a fifth force because we can’t necessarily explain this behavior with the four forces that we know” of nature, which are gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces, said Mitch Patel, a physicist at Imperial College. . From London to the British Gazette”Watchman“.

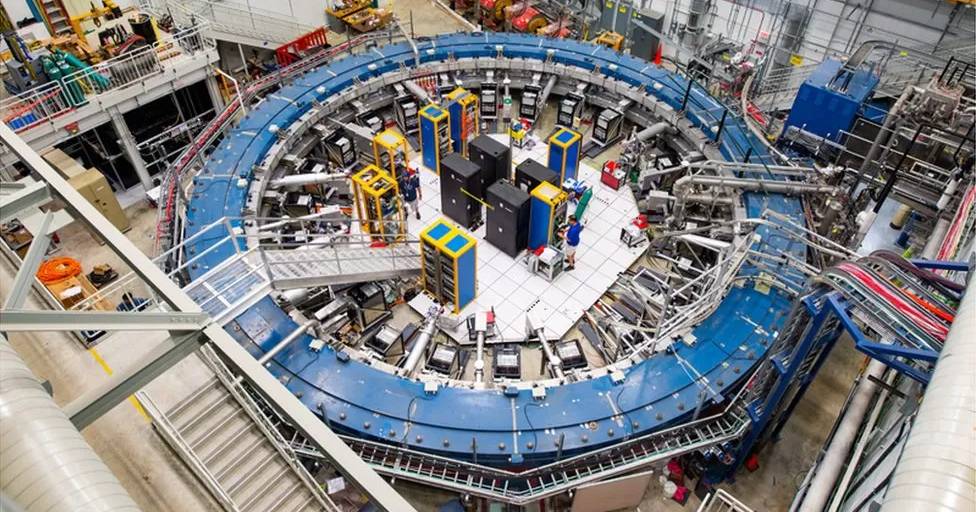

The experiments were carried out at the Fermilab particle accelerator in the United States, and showed an unprecedented oscillation of muons around the axis of the magnetic field. Muons are subatomic particles that have a positive or negative electrical charge equal to that of an electron but are about 200 times heavier.

The researchers then discovered that these particles oscillate faster than expected, and behave in a way that cannot be explained by the current theory of the so-called “Standard Model of particle physics”, possibly due to the influence of a new force.

“Measuring behaviors that do not match the predictions of the Standard Model (…) will be the starting weapon for a revolution in our understanding, because the model has withstood all empirical tests for more than 50 years,” added Mitch Patel.

As John Butterworth, Professor of Physics at University College London, explained, for the same newspaperThe oscillations are due to the way the muon interacts with the magnetic field. “It can be calculated very precisely in the Standard Model,” but when “the measurements don’t match the prediction, this can be a sign of an unknown particle that could, for example, be a carrier of a fifth force,” he noted.

More hard evidence is needed to confirm these findings, but the trials date back to 2021. Since then, the researchers have run more tests, collected more data and determined “measurements with more precision than ever before,” confirmed Brendan Casey, senior Scientists at Fermilab, at BBC News.

“Coffee trailblazer. Social media ninja. Unapologetic web guru. Friendly music fan. Alcohol fanatic.”