Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of amazing discoveries, scientific discoveries, and more🇧🇷

CNN

🇧🇷

Scientists have identified two minerals never before seen on Earth in a 15.2-metric-ton (33,510-pound) meteorite.

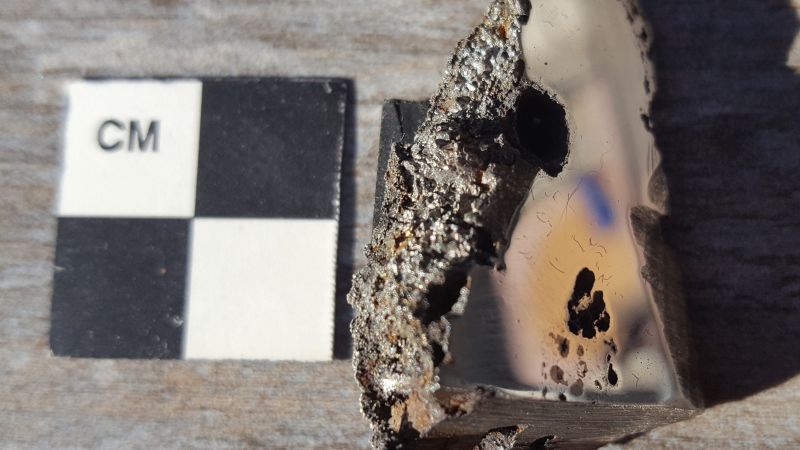

The minerals came from a 70-gram (about 2.5 ounce) piece of meteorite discovered in Somalia in 2020 and is the ninth-largest meteorite ever found, according to New release from the University of Alberta.

Chris Hurd, curator of the university’s meteorite collection, was given samples of the space rock so he could classify them. While examining it, something unusual caught his eye – the microscope did not recognize some parts of the sample. He then sought advice from Andrew Lowcock, head of the university’s Electron Microprosthetics Laboratory, as Lowcock had experience describing new minerals.

“The first day he did some analyses, he said, ‘You have at least two new minerals in there,’” Hurd, a professor in the university’s department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, said in a statement. “That was unusual. Most of the time it takes a lot more work than that to say there’s new metal.”

The name of one of the minerals – elaliite – was derived from the space object itself, which has been called the El Ali meteorite since it was found near the city of El Ali in central Somalia.

The second flock is named Elkenstantonites in honor of Lindy Elkins-Tanton, vice president of the Planetary Initiative at Arizona State University. Elkins-Tanton is also a wise professor in the university’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and principal investigator for the upcoming NASA. Self task – a trip to an asteroid rich in minerals orbiting the sun between Mars and Jupiter, according to the space agency🇧🇷

“Linde has done a lot of work on how planetary cores form, how iron and nickel cores form, and our closest isotopes are iron meteorites,” Hurd said. “It makes sense to name a mineral after her and to recognize her contributions to science.”

The approval of the two new minerals by the International Mineralogical Association in November of this year “suggests that the work is strong,” said Oliver Schooner, a mineralogist and research professor in the Department of Geosciences at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

“When you find a new mineral, it means that the actual geological conditions, the chemistry of the rock, were different from what was found before,” Hurd said. “That’s what makes this exciting: In this particular meteorite, you have two officially described minerals that are new to science.”

Lowcock’s quick identification was possible because similar minerals had been created synthetically before, and he was able to match the composition of the newly discovered minerals to their man-made counterparts, according to the University of Alberta release.

“Materials scientists do it all the time,” said Alan Rubin, a meteorite researcher and former assistant professor and researcher in geochemistry in UCLA’s Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences. “They might come up with new compounds—one, just to see what is physically possible only as a research interest, and the other…they’ll say, ‘We’re looking for a compound that has certain properties for some practical or commercial application, like conductivity, high voltage, or high melting temperature.'” ”

“It is by chance that a researcher finds a mineral in a previously unknown meteorite or terrestrial rock, and many times later the same compound will be created earlier by material scientists.”

Schöner said both of the new minerals are iron phosphates. Phosphate is a salt or ester of phosphoric acid.

“Phosphates in iron meteorites are by-products: they are formed from the oxidation of phosphates … and they are rare primary components of iron meteorites,” he said via e-mail. Thus, the two new phosphates tell us about the oxidation processes that took place in the meteorite material. It remains to be seen if oxidation occurred in space or on Earth after the collapse, but as far as I know many meteorite phosphates formed in space. In any case. It is likely that water was the reagent that caused the oxidation.”

The findings were presented in November at the University of Alberta’s Space Exploration Symposium. The findings, Rubin said, “expand our perspective on what natural materials can be found and formed in the solar system.”

The divine meteorite from which the minerals came, Hurd said, appears to have been sent to China in search of a buyer.

Meanwhile, researchers are still analyzing minerals — and possibly a third element — to see what state the meteorite was in when the space rock was formed. He added that the newly discovered minerals could have interesting implications in the future.

“When a new material is known, materials scientists also get interested because of its potential uses in a variety of things in society,” Hurd said.

“Coffee trailblazer. Social media ninja. Unapologetic web guru. Friendly music fan. Alcohol fanatic.”