Researchers at the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands use the Atacama Large Millimeter/ Sub-millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chilediscovered dimethyl ether around the young star Oph-IRS 48. With nine atomsthis is the largest molecule ever identified in a planet-forming disk to date.

According to the scientific article published today, Tuesday (8) in the magazine Astronomy and astrophysics To describe the discovery, dimethyl is a precursor to organic molecules such as methane, which in some cases may be an indication of life.

publicity celebrity

Also according to the study, dimethyl ether (CH3OCH3) is an organic molecule commonly used in cloud-forming clouds. stars, but have never been found in a planet-forming disk. The researchers also made a tentative discovery of methyl formate (CH3OCHO), a complex molecule similar to dimethyl ether that is also a “building block” for larger organic molecules.

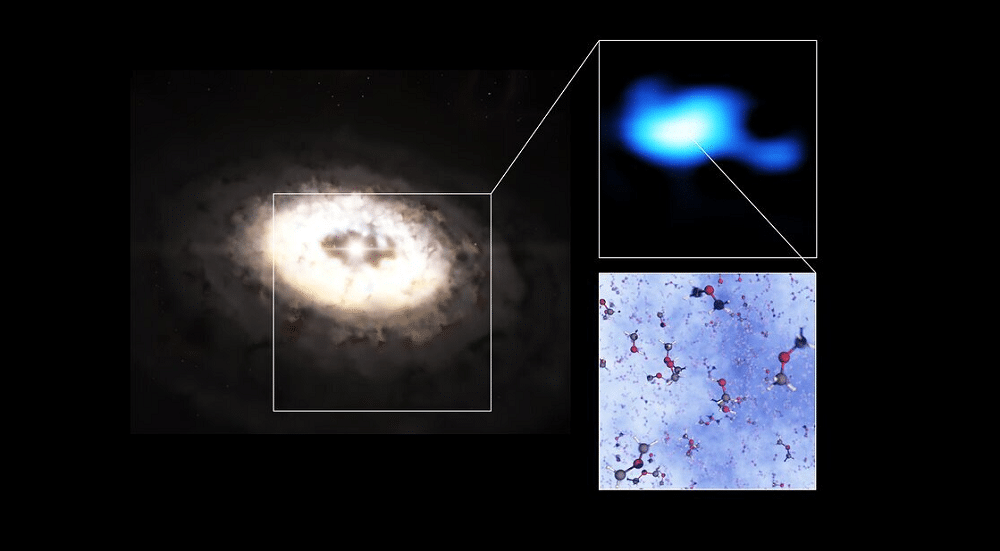

It is located 444 light-years away from a land, in the constellation Ophiuchus, the star Oph-IRS 48 has been the subject of numerous studies because its disk contains an asymmetrical “dust trap” shaped like a cashew bean. This region contains a large number of millimeter dust grains that can coalesce and grow into kilometer-sized objects such as comets, asteroids, and even potential planets.

Chemical reactions between simple molecules and dust grains lead to more complex ones

“From these results, we can learn more about the origin of life on our planet, and thus gain a better idea of the possibility of life in other planetary systems,” said lead author Nashanti Pronkin, a master’s student at the Leiden Observatory. In a statement issued by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). “It’s very exciting to see how these results fit into the big picture.”

“It’s really exciting to finally discover these larger particles in the disks. For a while we thought it wouldn’t be possible to observe them,” says co-author Alice Booth, who is also a researcher at the Leiden Observatory.

Many complex organic molecules, such as dimethyl ether, are believed to originate in star-forming clouds, even before the stars themselves are even born. In these cold environments, simple atoms and molecules like carbon monoxide stick to dust grains, form a layer of ice and undergo chemical reactions that lead to more complex molecules.

Read more:

The researchers found that the dust trap in the Oph-IRS 48 disk is also an ice reservoir, harboring dust grains covered in this complex-particle-rich ice. When the young star heats up the ice into gas, the inherited dimethyl ether molecules are released from the cold clouds and become detectable.

“What makes this even more exciting is that we now know that these larger complex molecules are available to feed planetary makers into the disc,” Booth explains. “This was not previously known, because these particles are hidden in ice in most systems.”

The discovery could give clues to the formation of prebiotic molecules on Earth

The discovery of dimethyl ether suggests that many other complex molecules commonly found in star-forming regions may also be lurking in the icy structures of planet-forming disks. These molecules are a precursor to prebiotic molecules such as amino acids and polysaccharides, which are some of the building blocks of life.

By studying their formation and evolution, researchers can gain a better understanding of how prebiotic molecules settle on planets, including our own. “We are very pleased that we can now begin to follow the full journey of these complex particles from the clouds that form stars, to the disks that form planets and comets. I hope that with more observations, we can come one step closer to understanding the origin of the prebiotic particles in our solar system,” says Ninke van der Marel, a researcher at the Leiden Observatory who was also involved in the study.

Have you seen our new videos on Youtube? Subscribe to our channel!

“Coffee trailblazer. Social media ninja. Unapologetic web guru. Friendly music fan. Alcohol fanatic.”