For those who don’t know, I worked for a few months at the University of Massachusetts, in the US, on an international radio astronomy project. The team here, in collaboration with the Mexican government, is developing a new camera capable of detecting gas and dust in galaxies tens of billions of light-years away, and I’m the only Brazilian on the team.

My participation was ensured by a grant from the US State Department, which funds the exchange of scholars, and ensures research mobility and internationalization.

Why am I talking about this? I was pondering this topic after a report I saw over the weekend about the current state of science in the country, and the challenges of rebuilding infrastructure that has been fraught over the past four years.

That’s right, investments in science have fallen a lot. We have labs with serious problems, scholarship values that are finally adjusting after 10 years of inflationary losses.

But we need more thinking.

It is not enough to increase the amount of investment if we do not think carefully about how to apply the money received.

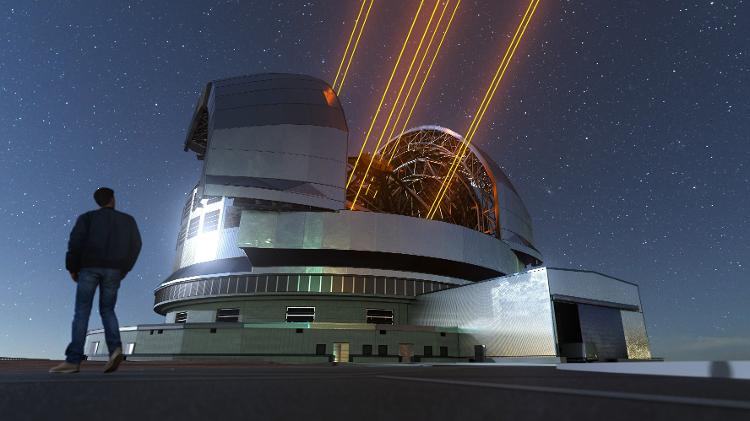

Going back to my project example, it’s an investment of about $50 million in radio astronomy hardware. Another project I’m coordinating — a camera for the world’s future largest telescope, the Extremely Large Telescope built by the European Southern Observatory — has even more funding.

However, Brazil has difficulties participating in similar international federations.

This is due in large part to a lack of planning and the scientific investability of the political landscape. When money appears, we must rush to spend it, because we don’t know if it will be there next year.

This creates significant obstacles for the participation of Brazilian scientists in large projects.

As I discussed in writing some time ago, cutting edge science is done on timescales of decades, not months. It requires long-term planning, which is almost impossible with such instability.

The end result is that the Brazilian flag is often seen as a secondary prop.

We often miss out on the opportunity to take on leadership roles in major international projects, and succumb to decisions made by major players over the years.

It is not enough to increase the funding available for science, we need to guarantee this funding for the next 10 or 20 years, ensuring a strategy that allows Brazilian scientists to plan their next steps.

James Webb started operating last year, but the design and construction began many years ago.

The Very Large Telescope will only be operational in 2028, and this camera only in 2031. Will I have funding to continue participating in the project until then? I can not say.

This funding is necessary to assemble a national team with the expertise to take advantage of the data at the opening of the camera.

During all these years it is essential to train students and collaborators so that our team will be on par with French, German and other colleagues when the crucial moment comes.

Likewise, here in the United States, I’m working hard to learn what I can, to bring that knowledge home, and to allow our National Institutes to be key players in these international collaborations.

This is the only way Brazil will take the leap needed to be treated as an equal on the world stage.

Only through long-term strategic investment can we participate in decision-making and play the necessary role.

Note 1: Not all science relies on this model of internationalization to ensure impact, it can come in other forms. But in astronomy, there is the fact that in such a globalized science, international collaboration is key.

Note 2: Although the name sounds like a joke, the instrument is actually called the Extra Large Telescope!

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”