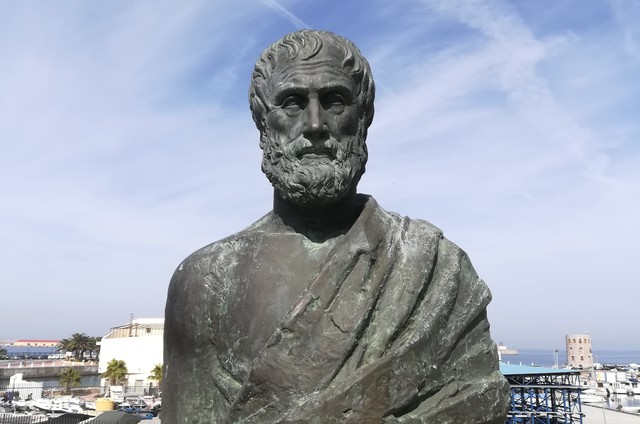

Marco Antonio de Avila Zingano

Among the writings sent to us as written by Aristotle is a short treatise commonly referred to as Categories. In this text, I will make some considerations about this treaty; Thus, the most appropriate title may be categories. But as we shall see briefly the subject of the categories, what is the category? – He will always be late and even, in the next text, he will be ahead of my analyses. In this way, “Categories (I)” is still an appropriate title, since studying the treaty published under this name we inevitably entangle the problem of classes as such.

The above-mentioned letter has met with extraordinary success in the history of philosophy. It has been widely commented upon, and we still have some of these: the smaller commentary that Porphyry wrote in question-and-answer form (the larger comment he wrote is lost); That Dexipo. that ammonium that Simplicio; That Philoponus. That Olympiodorus. That David (Elias), plus a very interesting comment from Anonymous. Other comments are lost – among them is the comment of Alexander of Aphrodisiac, which will certainly teach us many things about him.

Shortly before Alexander, the physician and philosopher Galen also produced a (missing) commentary, and mentions another—also missing—such as that of Adrastus and Aspasius. And there are still others – such as Boethos of Sidon (Aristotelian, not Stoic), for example, which appears prominently in later comments and is quoted with great respect. Not all were of a properly exegetical or exegetical nature, as some wrote to combat the Aristotelian orthodoxy defended there—among them, the writings of Lucius and Nicostratus were perhaps the most ferocious, though certainly not the most effective in this direction. Indeed, Porphyry, who was a disciple of Plotinus, edited the latter’s works, organizing his essays into six groups with nine treatises each, the Enneads; In the sixth and final ninth we see Plotinus attacking the doctrine of the Aristotelian categories, limiting their scope (if they are valid, they are valid only for the intelligible world; for the intelligible world it is Plato who sets the tone for the sophist and the great types), however, it must be corrected (Plotinus rethinks In them there are only five and five categories of the reasonable world, and not ten, as Aristotle suggested). There are also apocryphal treatises, likely written in the last century of Antiquity, attributed to Architas of Tarantum, the Pythagorean philosopher who would have influenced Plato. Simplicius cites him respectfully and takes Aristotle’s writings as being heavily influenced by the studies of this philosopher; Today we can show that history is the opposite. However, it should be noted that one of these letters attributed to Archytas on the categories is particularly interesting, in which the forger demonstrates a good knowledge of Aristotle’s text.

Why did Aristotle’s thesis arouse so much interest? His study was part of scholastic studies in the late Hellenistic period, especially in the Neoplatonic school, but this cannot be an answer to our question, because it was not important because it was studied with a fine-tooth comb, but was studied with a fine-tooth comb for a reason. The reason motivates a lot of effort on the part of a lot of people. You might want to start by trying to answer the question of when did you start getting so much attention? In fact, there is an event in antiquity that has to do with our topic. In the last century of the Archaic period, Andronicus of Rhodes edited the works of Aristotle into a copy that still serves as the basis for modern editions. The history of Aristotle’s texts – their supposed disappearance shortly after Aristotle’s death and their return to circulation at the hands of Andronicus – is too fascinating to believe in every detail. However, there is still the fact that there is an event to this remake, which certainly adds fuel to the fire, but may not have been the one that spurred the rebirth of these studies. Indeed, one can discover an important intellectual turn occurring precisely in this period, of which this new edition may not be its origin, but its tributary. This shift of thought can be called the age of commentators – roughly, but only approximately, at about this time philosophical questions were dealt with in the context of commentary and interpretation of ancient works (and the ancient works must be understood primarily through those of Plato and Aristotle). Of course, such etiquette is misleading and unfair in some respects; To take just one example, Boethos does philosophize—and even introduces a strong materialistic bias into the ancient Aristotelian morphology—while commenting on Aristotle’s work. Roughly speaking, however, there is a change in tone that is important to note. Commentary on “classical” authors (Plato and Aristotle) and philosophy was not seen as opposing. Let’s take a very famous example of Plotinus, who, active in the third century of our era, sees himself as an interpreter of Plato, but in his interpretation of Platonism creates a new philosophy of his own. Nevertheless, our literature is useful, because it establishes a position of reference and, at times, a reverence for ancient texts that did not exist before, or were not as sharp.

Explaining the birth of a new intellectual position is always complex and requires historical data that are often identified outside the realm of culture and philosophy. The fact is that the abundance of commentaries goes back to the last century of our era, a particularly turbulent century in the history of Rome, if Rome lived in any untroubled period after it imposed itself on the history of the ancient world. Let’s be humble and go back to the office where Andronicus works. He prepares an edition of Aristotle’s Works in which logical texts are placed in the first place due to their function as necessary tools for all intellectual analysis. Among these tools, our small treatise comes to the fore. After all, it deals with the terms separately. With the tangle of terms, we have the assumptions that De Interprete holds. With the propositions taken as an introduction to the argument, we have studies of analogy first, and secondly the study of forms of deduction; Then, according to the study of the scientific knowledge that arises from it, provided that the assumptions made as premises of the arguments meet certain conditions (such as being first and true) and that the arguments themselves are organized in a certain way (such as providing reason in the middle range of the analogy). Then we have the study of a syllogism whose premises are propositions deemed true–what Aristotle calls an endoxon, a famous premise, which may be true, but appears as a premise to the argument not because it is true, but because it is. famous to be so. These are the so-called dialectical syllogisms, the topics of which describe the different styles of arguments (which Aristotle calls topoi, “places” or “structures of argument”). Finally, it is worth examining the Aristotelian arguments, where something makes them only superficially good, because they are in fact systematically misleading, a topic to which the thesis of Sophistic Refutation is devoted. This concludes the first part. After that, we proceeded to the study of the sensible world, and the first text was the no less famous Aristotle’s physics. Thus, the Treaty of the Categories appears at the beginning of the beginning – as it is even today; It is clear that the reader desiring to know Aristotle begins at the beginning: then opens the treatise on the categories and begins to study them…

You said it was a small treaty. In fact, it only takes 15 pages in the Bekker version (compare 80+ pages in physics, for example). And it could have gotten smaller if we had followed Andronicus’ advice. In fact, Andronikos considered the third part, called Postpraedicamenta (which occupies chapters 10 through 15, approximately 5 Bekker pages), as false. For him, someone tried to stick a third part into the treaty, which would have nothing to do with the above but, once submitted, would justify attributing the whole treaty to Pro ton Topôn, “before Topoi”. This was the other title given to the treatise in antiquity and it was meant to indicate that this treatise was a precursor to dialectical studies – so it should not be read in an ontological key, but merely as a provision of the basic material we use. In our dialectical disputes, in which the famous prevails, and not the real (this is the title that holds the new French edition, published in 2001). With the excision of Andronicus, nothing justifies such a thesis, and we shall take the thesis again as a study of the terms of a proposition, with a preparatory purpose of science, and not merely as a discussion. Indeed, if Andronicus’ crosses prevailed, we would also have fewer texts, since Andronicus considered that De’s interpretation was also not of Aristotle, because he began with a treatise (Concepts are feelings in the soul) that was expressly rejected in De anima, an undeniable work. From Aristotle’s pen (in De anima, in fact, the concepts generated by thought are said to contradict the statements provided by sensation, and only the latter provide the Pathêmata or emotions).

All this to say that the birth of the work is already beset by controversies. As we shall see, the discrepancies will only increase.

Marco Antonio de Avila Zingano is Professor of Ancient Philosophy at the University of the South Pacific

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”